Essays by Ursula Le Guin…

This last week I’ve been reviewing final versions of several lectures I delivered to students at the Vermont College of Fine Arts during the seven years I taught there. Seven years means fourteen semesters, with a few semesters “off duty” when I was excused from delivering a full-blown lecture.

One semester I helped organize a Good vs. Evil Day – Tim Wynne-Jones and I asked students to think about villains and heroes, and about writing characters who were either flawed good guys or appealing bad guys – the theory being that no person is either completely good or completely bad. Villains are more interesting if they see themselves as heroes (in the style of Inspector Jauvert of Les Miserables, who believes that his love of law and order means he is always “keeping watch in the night” against chaos and corruption) and heroes are definitely more interesting if they’re three-dimensional, if they’re good but at the same time flawed or complicated (“The self is always under construction…” says Peter Turchi, and “…the multiplicity of selves is what allows change.” ) Or, as Walt Whitman put it, “I contain multitudes.” Students had fun with that presentation, but it seemed a given – “Deepen your characters” is not exactly new advice – and I didn’t ever consider repeating it.

Essays by Katherine Paterson…

Another semester I worked to put together a workshop (later repeated with students of the regular MFA writing program) about the need for play in works of poetry and fiction, and how artificial “constraints” allow for a game-playing mind-set. We looked at the rules of poetic forms – a sonnet, a villanelle, a sestina, a double abecedarian. Trying to stay “inside the lines” counter-intuitively frees us up, that’s what I was trying to say. We end up producing work that surprises us, and everyone knows that “no surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader.” So we played and wrote responses to “challenges” with devilishly hard constraints (Ever try a “syntax map”? If not, count yourself lucky. Ever translate work without knowing the original language at all?) I had high hopes for that presentation – but it didn’t come together the way I expected it to. If the students had all been writing poetry, it might have worked. But it was hard to convince fiction writers that constraints would improve their fiction. Win some, lose some.

Essays by Paula Fox, Jill Paton Walsh, Virginia Hamilton, Susan Cooper, E. L. Konigsburg, Arnold Lobel, Myra Cohn Livingston, David Macaulay….

Most semesters I delivered a straight-forward lecture from a podium. I started my first semester at VCFA with a lecture about poetry, since that was my “specialty.” Later I moved on to a lecture about the need to be a “flaneur” and wander the neighborhood/city/world with every observational skill on the alert, eavesdropping, following people (a la Maira Kalman), taking photos. That lecture was well-received, but I realized I couldn’t ever quite predict what the students were hungry to hear or learn about. My solution to that was to choose my topics based only on whatever interested me at the time. I had just read Edmund White’s The Flaneur: A Stroll Through the Paradoxes of Paris, so the art of the flaneur was what my students got.

One of my most successful lectures – that is, the one students responded to with the most enthusiasm – was about maps in works of fiction. It seemed to me that quite a lot of student work I had been reading had forgotten that stories and the characters who inhabit them take place in real space, and if you don’t give your characters a landscape and a place to stand in that landscape, then they are literally not “grounded.” Students brought maps of the locales in which their stories were unfolding. What a treat! My favorite was a completely black map with “aromas” attached (kind of scratch-and-sniff-ish) because the student’s story involved anthropomorphized insects with great charm and personality and a well-developed sense of smell. The result of that lecture was published in The Horn Book, though the magazine couldn’t publish the maps I showed on a large screen to students – maps from Treasure Island, Peter Pan, Ramona Quimby’s neighborhood, the 100-acre wood of Winnie-the-Pooh, Narnia. and many others.

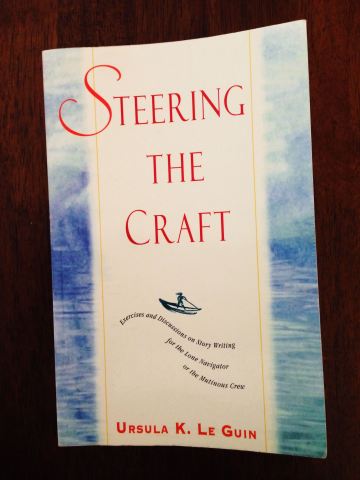

I delivered one lecture that I thought would go over like a lead balloon, about the “artful sentence,” because I’d been reading Virginia Tufte’s wonderful book of the same name.

I pulled examples from the work of M.T. Anderson (The Astonishing Life of Octavion Nothing, Traitor to the Nation), Margo Lanagan (Tender Morsels), and Sandra Cisneros (The House on Mango Street.) I beat my usual drum about how sentences actually have rhythm the way music does; somehow, the students just lit up and loved it. What a surprise that was. If students tripped consistently over a single stumbling block, it was the sound quality of their sentences. I assumed, going in to that lecture, that they weren’t interested. But apparently what I said sparked a little flame. For beginning writers, so much effort goes into moving forward with plot that the quality of the language gets shoved aside. So I talked about flow and fluidity, and about the effect of hard stresses, and accented syllables that echoed the action itself.

My favorite lecture, though – the one I had the most fun working on and the one that reflected a years-long obsession of my own – was titled “Who Am I? What the Lowly Riddle Reveals.” Students read the packet description and expected “What’s black and white and read all over?” puzzles, and instead I wanted to help them consider metaphorical thinking – the art of understanding sub-surface connections between one thing (an object?) and another (a state of mind or emotion?) I talked about metaphors being the equivalent of riddles, and about how to keep metaphor-making fresh so that our writing will be exciting. That lecture was later published in Numero Cinq magazine.

My last lecture before retiring was about flash fiction. I was interested, and it was a lot of fun, since it was a plea once again to play with form. But I relied heavily on excerpts from other people’s work, and though the fun showed up, my own imaginative thinking was tamped down.

Just today I sent two of those lectures in, polished up into essay form (drop the jokes, forget the slideshow) for a possible presentation to editors of a book anthologizing craft lectures from the faculty of VCFA. My creative interest really has been in essays lately rather than in stories. I can feel a soft wind pushing my boat that direction.

And here at Books Around the Table I want to encourage readers who feel that same wind to take a look at putting on the hat of an essayist. It’s through essay writing that I learn more and more about writing – by having to articulate a specific aspect of craft, I make myself more aware of what’s at work in not only other people’s writing, but in my own.

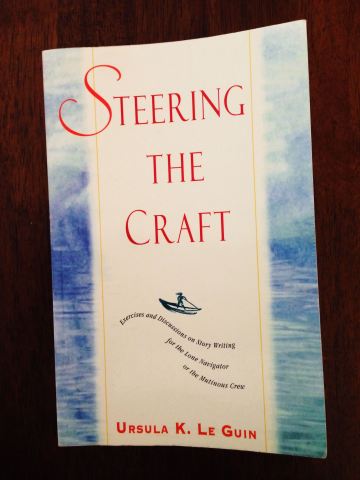

Next time you read a book of essays about writing (not the how-to kind but the why-to) see how the author is doing what he or she does. What makes it more interesting than a textbook? What might you say about the same topic? I just finished a glorious craft book – absolutely delightful – called A Muse and a Maze: Writing as Puzzle, Mystery and Magic by Peter Turchi (author of Maps of the Imagination. ) It’s a perfect model. Read it. Dissect Turchi’s technique. Think about the obsession that drove him to write a whole book about how writing is similar to (but not the same as) the work of a magician like Houdini or a puzzle-maker like Will Shortz. Then think about your own obsessions. What do you want to figure out?

It’s not the essay writing that you had to do in college which, at the time, might have resembled a trip to the dentist – you groaned and got it done, but it didn’t fill you with pleasure. Instead, see the art of essay-writing as an opportunity for growth as a creative writer. The research, the re-reading of favorite books (reading to understand how a certain effect is achieved), the organizing of thoughts, the actual writing, all of it is pleasurable now. Something about good old prose is similar to a Shaker chair, if you know what I mean – unfussy, direct, clean, spare, useful, graceful. It’s been good for me. It might be good for you, too.