Kelly Barnhill, author of this year’s Newbery winner, The Girl Who Drank the Moon, says her book began with a vision that literally stopped her in her tracks:

I was out for a run, and I had this image appear in my head, unbidden, that was so shocking to me that I had to stop in my tracks. It was of this four-armed swamp monster with a huge tail, and extremely wide-spaced eyes…and these big, damp jaws and it was holding a daisy in one hand and was reciting a poem…

That’s one way ideas come. A gift from the universe. And there are the good times when they seem to come crowding into your mind. But sometimes they don’t come at all. That’s what I want to write about today–what do you do when the ideas aren’t popping.

First, let’s get in the right frame of mind.

There are two types of brain waves associated with generating creative ideas, especially the kind that seem to come from nowhere. The ones that just rise up into your conscious mind. They are alpha and theta waves.

Alpha waves are a function of deep relaxation. In alpha, we begin to access the creativity that lies just below our conscious awareness. It is the gateway, the entry-point that leads into deeper states of consciousness. And they often rise into consciousness on that walk, in the bath, on a car ride.

A deeper state of consciousness is signaled by theta waves. It is also known as the twilight state–which we normally only experience fleetingly as we rise up out of sleep, or drift off to sleep. Probably most of us have been jolted occasionally by a sudden idea or solution or vision in these moments.

But how can we get into these creative states?

Artists through the ages have tried! They’ve called on the gods, made deals with the devil, called on love, passion, nature, drugs, alcohol and madness.

But actually those alpha and theta waves? They like certain conditions, especially alpha.

Your brain waves will tend to fall in with a dominant rhythm in your environment: a drumbeat, a heartbeat, the fall of your footsteps—they call it entrainment. So the creative muse loves rhythmic activity: music, walking, chopping vegetables, riding along in a vehicle.

Mozart said, “When I am traveling in a carriage, or walking after a good meal, or during the night when I cannot sleep; it is on such occasions that ideas flow best and most abundantly.”

It’s no coincidence that Barnhill’s vision of the swamp monster came to her during a run.

But let’s say, you’ve walked your feet off, bathed till your skin is a prune, chopped broccoli for hours, and you still got nothin’. There are also more deliberate ways to generate ideas. Let’s start with this simple formula for a story:

A (character) who (core trait) wants (goal plus hidden need).

The core trait is a simple, quick way to give your character a personality. It’s a good way to think about picture book characters who need to be developed quickly and simply.

So the formula for my book A Visitor for Bear might be: a bear who is grumpy wants to be left alone (but the truth is he needs a friend.) The formula for Wanda Gag’s Millions of Cats might be: a couple who are old want a cat (but the true need is companionship or something to care for.)

Of course, these formulas are for books that have already been worked out, and A Visitor for Bear actually was one of those “just popped into my head” ideas, but let’s say you really are at a loss for an idea. So let’s look around and just grab something.

“A cat who is ugly wants to catch a mouse (and I don’t know the true need yet.)”

Okay, I truly did just grab this out of my head. Let’s see what happens if we work with it. I especially like to play with the core trait, because how a character is challenged or changed is what makes the story interesting.

1.Make the core trait conflict with the goal/need.

For example, in Millions of Cats most couples might look to have a child to meet that need to have companionship or something to care for—but their core trait is that they are old. Not only does this heighten their loneliness, it means having a child is not possible. It ups the stakes and means there will be obstacles to overcome in order to not be lonely in their old age.

2. Work with an unusual trait:

Rather than creating a character who is easily scared (a familiar trait), how about someone who loves to scare others?

Rather than someone who’s nice, create a character who’s grouchy (That’s my bear in A Visitor for Bear.) Rather than a child who is scared about the first day of school, a child who can’t wait! Rather than a child who won’t eat his vegetables, a child who is a vege fiend!

3. Combine disparate traits:

A gentle giant. A kind witch. A pacifist bull. A mighty ant.

4. Put two characters with conflicting traits together:

A cheerful mouse and a grumpy bear

You can also work with plot.

5. Set up an unlikely or improbable goal:

A cow who wants to be a ballerina. A horse who wants to drive a car. Your character can be fairly ordinary but there will be story conflict and reader interest because of the improbable goal.

So let’s start messing around with that idea about an ugly cat wanting to catch a mouse. Notice it’s a mundane familiar goal. Picture books have to be simple so if I combined an odd core trait with an unlikely goal it can get complicated. An ugly cat who wants to go to the moon. It might work, but it becomes unclear what’s the real issue of the story.

So I’ll stick with “ugly cat wants to catch a mouse” and start to play with the options. An ugly cat: well, that’s a bit unusual. We don’t often deal with an ugly character in a picture book. But the story immediately suggests humor and the character is not human, so we can have fun with it.

Does his core trait (ugly) conflict with the cat’s desire to catch a mouse? Maybe. Maybe he’s so ugly he scares away mice before he can even get close. Okay that seems funny to me. So I can go with that.

Does his core trait (ugly) conflict with the cat’s desire to catch a mouse? Maybe. Maybe he’s so ugly he scares away mice before he can even get close. Okay that seems funny to me. So I can go with that.

Since he’s always scaring away his intended prey, what does he do? Put on a mask? Put a bag over his head? Try to creep up on mice backward? Now I’m starting to see the obstacles that will make up my plot.

Can I take advantage of two unlikely characters together? Cats and mice aren’t known to be friends. Cats are the predators. Mice, the prey. Cats big, dangerous, brave, graceful. Mice, small, scared, hiding, weak. I could maybe play off those stereotypes or start flipping them in some way. A big mouse. A tiny cat. But I need to ground my story in that core trait. What the one thing I know for sure about my particular cat. He’s uncommonly ugly.

Is my mouse perhaps uncommonly handsome? Or is he the world’s ugliest mouse? Do they have that in common?

Since this is child’s picture book, I know I want to drive it to a happy ending (although if the tone is exactly right, you could perhaps have a more macabre ending like I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen. But that is a rare exception.) So now I’m liking the idea of the having the world’s ugliest mouse because I can see friendship there. That’s probably my cat’s true need—friendship or acceptance.

To really develop this story would take a lot more time and thinking. And, more often than not, you might find your story idea ultimately doesn’t work or doesn’t really hold your interest. But generating a story idea in this very deliberate way might get the story making machine inside your mind turning over again.

So grab a random character, a trait and a need and start walking!

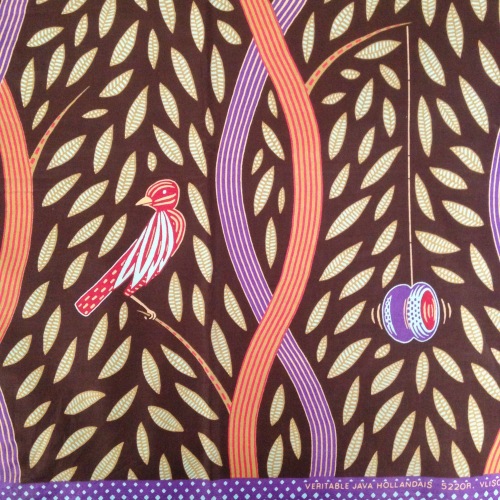

I always like the ones with birds.

I always like the ones with birds.

![image1[11]](https://booksaroundthetable.files.wordpress.com/2017/05/image111.jpg?w=500)

Julie and I even went to Helmond outside of Amsterdam to visit the Vlisco factory for a bit of viewing and shopping.

Julie and I even went to Helmond outside of Amsterdam to visit the Vlisco factory for a bit of viewing and shopping.