A while ago I wrote about a book a friend showed me from her childhood.

This post is about a book that another friend showed me from her childhood, but this book brought back flashes of memory as soon as I saw it. It was a book from my childhood as well, long forgotten.

ANT and BEE: An Alphabetical Story for Tiny Tots (Book I) by Angela Banner, illustrated by Bryan Ward, first published in the U.K. in 1950.

There is nothing quite like the feeling of recognition that happens when you come upon a book that you haven’t seen in maybe, fifty years. It is like the way a certain scent will suddenly take you back to a long-ago visited place; little bells tinkling in the back of my brain announcing the arrival of an old friend.

The book is small – roughly 3 ½ x 4 inches – which suits it’s subject matter and adds to its charm. It is straightforward yet silly. Realistic yet completely implausible. But it is not cute. It maintains a dignity in spite of its diminutive size and subject. Maybe it’s the hats…

The opening endpaper states:

Ant and Bee is a progressive ABC written as a story with simple words, some of which are printed in red and some in black. The words in red are to be called out by the child when it has learned to spell them out and to pronounce them. A grown-up then completes the sentences by reading the words in black as soon as the words in red have been called out by the child. Encouraged by the grown-up, the child will soon learn the words which it must read before the story can progress. In this way, the child will feel an interest in helping to tell the story and will, at the same time, gain confidence in reading and building up a small vocabulary.

That’s a lot of instructions for such a small book. Apparently Banner wrote the book as a way to help her son learn to read. This probably helped sell the book in the ‘50s, but it seems a bit bossy for today’s grown-up readers.

Here is ANT.

And here is BEE.

They live in a CUP.

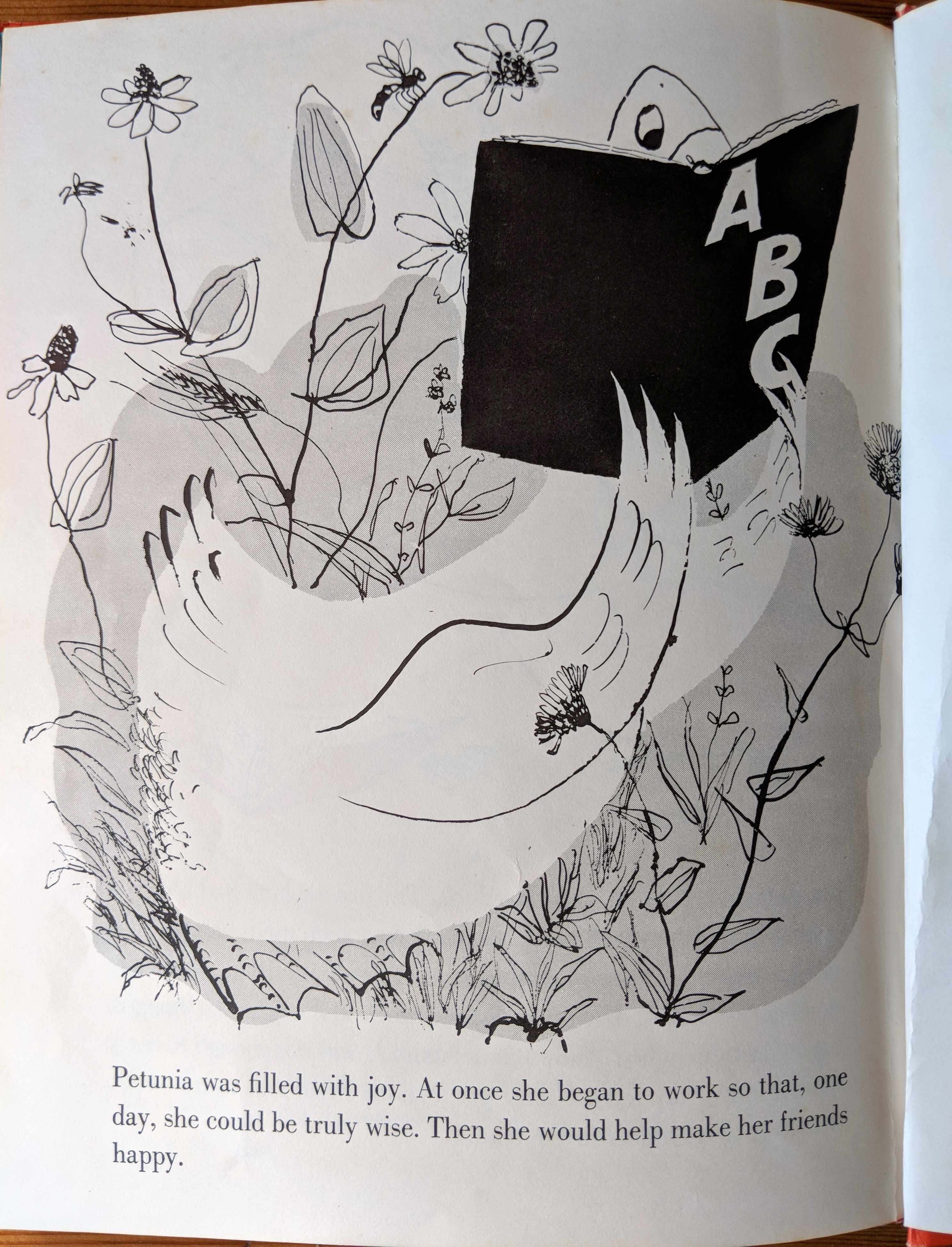

And so on. Here are more images that I particularly like.

I loved finding this book again. But do I love this book now because I liked it when I was young? Is it charming only because of nostalgia? And I wonder what I often wonder when I read a book published before 1980: Would it be published now?

When I was cleaning off my parents’ bookshelves, I came across a book, Kay Nielsen: An Appreciation, by

When I was cleaning off my parents’ bookshelves, I came across a book, Kay Nielsen: An Appreciation, by