Author George Saunders

“What does an artist mostly do? She tweaks that which she’s already done.” So says George Saunders in his brilliant essay on writing published March 2017 in The Guardian newspaper. For me, it captures the process of writing, the feeling of writing, like no other essay I’ve read.*

Saunders discusses many wonderful things in “What writers really do when they write,” including how he developed his acclaimed first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo. (Saunders usually writes short stories.)

One thing that jumped out at me is his description of how he revises his work; what he does mentally.

Write-or-wrong-o-meter

“I imagine a meter mounted in my forehead, with ‘P’ on this side (‘Positive’) and ‘N’ on this side (‘Negative’). I try to read what I’ve written uninflectedly, the way a first-time reader might (‘without hope and without despair’). Where’s the needle? Accept the results without whining. Then edit, so as to move the needle into the ‘P’ zone.”

I do something similar, but I have never made it as concrete as a forehead meter. It’s a gut thing for me. But I think we all know what Saunders is talking about. That knowing that we like it, that it works, or that niggle that we desperately want to ignore that tells us “this could be better.”

It did take me awhile to recognize that gut feeling–to trust that this did need changing or that this really did make the story better. So, if you find it hard to tell where the meter is, other than perhaps permanently stuck in “this is crap,” focus on the niggle part. The thing that catches at you but that makes you want to say, “Maybe this doesn’t matter” or “Maybe the reader won’t notice.”

In other words, start with what you don’t want to be true.

Still I like that he asks only that the needle move into the ‘P’ zone. Not that it top the charts. At least, my zones would not be one fixed point of ‘P’ or ‘N’, but rather exactly that—zones. A band. Of course, you would want to move the needle as far into “Positive” as possible but I’m not sure you could hit the top of the zone with every sentence, every passage.

In fact, I worry that the work would become stilted and brittle if you attempted that. I don’t think perfection is a good standard to set for art.

And that’s not the standard that Saunders sets, although I think he thinks that you’ll get close if you just do this: “Enact a repetitive, obsessive, iterative application of preference: watch the needle, adjust the prose, watch the needle, adjust the prose… through (sometimes) hundreds of drafts. Like a cruise ship slowly turning, the story will start to alter course via those thousands of incremental adjustments.”

I also love what he has to say about how this process respects the reader.

“We often think that the empathetic function in fiction is accomplished via the writer’s relation to his characters, but it’s also accomplished via the writer’s relation to his reader.”

The changes Saunders makes are based on the idea that “if it’s better for me over here, now, it will be better for you, later, over there, when you read it. When I pull on this rope here, you lurch forward over there.”

But rather than a clumsy place where you pull ropes and your reader lurches, Saunders says you’ll end up in a “rarefied place. (rarefied in language, in form; perfected in many inarticulable beauties—the way two scenes abut; a certain formal device that self-escalates; the perfect place at which a chapter cuts off)…”

Oh, don’t we all have those bits of craft and serendipity in our writing that so please the artist in us? And according to Saunders they will be pleasing to the reader, too.

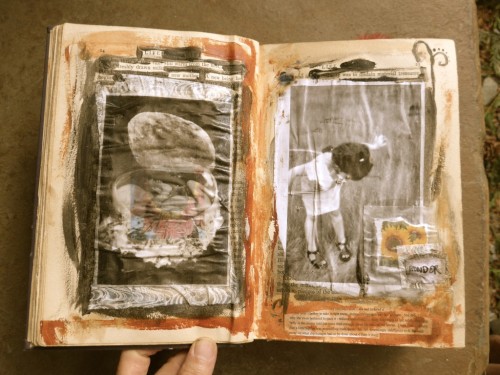

Illustration by Noemi Villamuza

“She can’t believe that you believe in her that much… This mode of revision, then, is ultimately about imagining that your reader is as humane, bright, witty, experienced and well intentioned as you… you revise your reader up…with every pass… ’No, she’s smarter than that. Don’t dishonour her with that lazy prose of easy notion.’

And in revising your reader up, you revise yourself up, too.”

There is a lot more in Saunders’ essay worth mulling over for any artist. You can check it out here:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/04/what-writers-really-do-when-they-write

And if you haven’t read Saunder’s short stories—get yourself to a library or bookstore soon. I think you’ll find your reader’s needle is well into the “P” zone.

*Thanks to Wendy Wahlman for handing me a copy recently. It was just what I needed at that moment.

It reads, “I could be a book, explaining everything on margins / I could be a photograph lifted from his heart, / Ah! Tomorrow”.

It reads, “I could be a book, explaining everything on margins / I could be a photograph lifted from his heart, / Ah! Tomorrow”.