I love the map you see above, especially its label: “Upside Down World Map.” As if our standard north-up/south-down maps are right-side-up.? According to whom? If I’m a bird, what perspective do I have? What if I’m walking on the moon? But I suppose standardizing the orientation of maps makes sense. They stabilize us as we spin through space, and as we spin through the spaces of our daily lives.

Many of you know already how much I love maps. I published an essay in the Horn Book about maps in children’s books (“Harbours That Please Me Like Sonnets: On the Pleasure of Literary Maps “) and I led a workshop at Vermont College of Fine Arts about making maps to reflect the location of our stories’ characters.

Robert Louis Stevenson’s Map of Treasure Island

For the last few days, I’ve been looking at a lot of maps while 1) flying from Seattle to Vancouver to London to Rome and 2) walking around Florence.

On the flight to London, in a brand new Boeing 777, passengers had available to them state-of-the-art seat-back touch-screens with every imaginable permutation of where the jet was headed as it crossed Canada, Greenland, parts of the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, Scotland and England. Not just the old, tired dotted line showing the progress of the plane. No, there were videos of sunsets and sunrises and Google Earth zoom-ins and zoom-outs, all of it with an inspirational glow, something golden on the edge of every horizon.

Forget the in-flight movies! I was glued to those maps, exploring every angle of this beautiful blue planet as I flew above it.

At Heathrow, maps on a smaller scale: airport maps, terminal and gate maps. Where to enter, where to exit, where to pick up bags, how to get to connecting flights. The omnipresent and omni-useful YOU ARE HERE dots which always save my sanity.

In Rome, there was a map as my husband and I walked into the Pincio, the park above the Piazza del Popolo, We headed for the old water clock and the view across the city to the dome of the Vatican.

In Florence (just arrived yesterday) we were given a map of how to get from the train station to the Piazza Santo Spiritu, onto which the windows of our little apartment open. Today, a map to the Mercato Centrale and the bus route up to Fiesole.

If you’re a writer, you probably care about maps. You think about the lay of the land, you think about settings. How do your characters move through the spaces they inhabit? Maybe you’ve made a map of their houses or their rooms? If not, try making one. Try making a map of their route to school or their route home from their local library. Don’t forget to add a compass – with it you’ll know where the sun rises and where it sets – does your hero wake up to sunshine? You’ll think about the flora of a given season – what is flowering in the yard, what is the look out the window at dusk if that window faces west?

Daphne Kalmar, one of my former students (who has become a good friend) once made a map of a story she was writing about three characters: a dragonfly, a fly, and a bee. The map was completely blacked out – it had only the “points of smell” that her characters might map out: honey, flower blossoms, garbage, dung….now that was a memorable map!

All this is by way of telling you to check out a recent article in The Smithsonian (has there ever been an issue of that magazine that didn’t inspire a poem?) about a man who is mapping river basins (among other things) around the world. Read it and be inspired to make a map of your own. Next time you’re at a school, spending time with kids, show them your map and ask them to make maps themselves of someplace familiar, or of a setting for one of their own stories. They (and you) might be inspired to write more stories about characters spinning through the daily spaces of their lives.

River Basin Map of Washington (Grasshopper Geography)

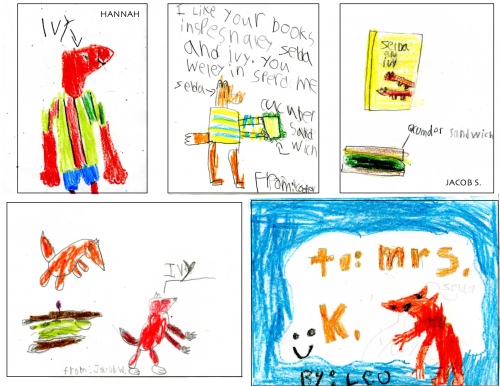

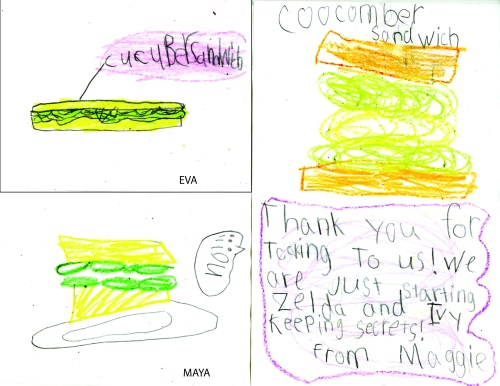

My Fox sisters are surely thrilled at the many portraits Mrs. Charnholm’s first graders included in their thank you notes.

My Fox sisters are surely thrilled at the many portraits Mrs. Charnholm’s first graders included in their thank you notes. more portraits —

more portraits —