While I am waiting for inspiration to strike and the next project to catch my attention, I find it helps to clean my studio. There, deep in a file drawer, I dug up these six illustrations: a sort of To Do List that aims to get your creative tail wagging.

It is often said that advice you give others is advice you need to hear. This is offered in that spirit.

I know BTC (Butt To Chair) is necessary, but regular hours at your desk are not the only hours that count.

Consider the impressionist painter Claude Monet. One day he was sitting in a green chair under a blossoming apple tree in his garden at Giverny. A neighbor came by and said, “Monsieur Monet, I see you are resting.”

“No, no,” answered Monet, “I am working.”

The next day when the neighbor walked by, Monet had set up his easel and was painting away. The neighbor said, “Monsieur Monet, I see you are working.”

“You are wrong, my friend,” said Monet. “Now I am resting.”

I envy Monet this overlap of work and rest. But I expect it was easier to achieve 120 years ago when the only interruption was an occasional neighbor walking by. These days, distractions are innumerable. So here’s my advice to myself: park it AND unplug. Whether you sit on a green chair in a beautiful garden or a worn chair in a Seattle studio, turn off the phone and email and texts etc. and give the work the time it deserves. BTC. There is no substitute. BTC means you show up daily, stay on task, and follow where your mind leads.

I love that there is a word for this in German: sitzfleisch, and also in Yiddish: yechas.

Does anyone keep a writer’s notebook anymore? I have a shelf full of past years’ notebooks, but these days I capture ideas in the NOTES section of my phone. Though I no longer keep a daily journal, I am still dedicated to recording story bits as they appear. Experiences, observations, memories; if it rings your story bell, write it down. Which reminds me of writer Brenda Guiberson’s advice to pay attention to the little hairs on the back of your neck. When they stand up, you have story material. Tell Siri to put it in NOTES.

Julie Larios once taught a class in the art of the flaneur. It was great practice in tuning in. She encouraged us to collect anything that engenders a writing response: photos, memories, questions, confusions, reactions to reading, stories held in objects, candy wrappers, newspaper clippings, feelings, fast-written lists. It’s all fodder, the puzzle pieces that may assemble as a story.

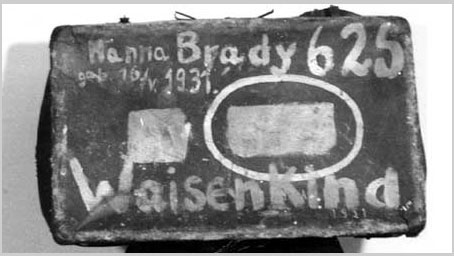

Humans are story people, readers as well as writers. Think back to the books you loved and figure out why they mattered to you. Then weave those qualities into your own work. For instance, my favorite childhood book was Betty McDonald’s Nancy and Plum about two orphaned sisters. I like to think some of the push and pull of sisterhood as well as the abiding sisterly love that is in Nancy and Plum shows up in my Zelda and Ivy series. It can be helpful to look back at old photographs and home movies to help remember the child you were.

I think it was Peter Sagal on NPR who said he chose his activities for their anecdotal value, planning ahead so he’d have interesting stuff to talk about. Why not? Research and adventures feed the story mill. Plus they can be entertaining and intriguing and often humorous. Full of story potential.

Give up on conformity. Don’t limit your imagination with the fear of acceptability. Receive with gratitude anything your imagination serves up: be it beautiful, ugly, absurd, outrageous or excessive. You can always revise later.

Lots of mistakes. Think of the Wright brothers and all their failed experimenting. Let yourself fail so that you can fly. You’ve probably heard the story retold in Art and Fear about the ceramics teacher who divided his students into two groups at the beginning of the semester. Students in the ‘quality’ group each needed to produce one perfect pot to get an ‘A’. Those in the ‘quantity’ group were graded by the weight of all the pieces they created, (i.e. 50 pounds = an ‘A’). Turned out (hah!) the students who made the most pieces also created the most successful ones, meaning they produced more schlock as well as more brilliant work.

WE SAID GOOD-BYE to our sweet Izabella on September 14. For sixteen and a half years she shared our lives, including hanging out with me while I worked. My students once gave me a pad of post-its printed: “Laura Kvasnosky…writing to the tune of dog snores,” which was often true. She helped create books in many ways: providing support and comfort and inspiration, and posing as a wolf for illustrations in Little Wolf’s First Howling. We are so grateful for all the time we had with her.

Rest in peace, sweet pup.

The same story structure is also found in a spare form in this poem from Julie L.’s Imaginary Menagerie, illustrated by Julie P.:

The same story structure is also found in a spare form in this poem from Julie L.’s Imaginary Menagerie, illustrated by Julie P.:

It was a luminous presentation, full of stories from her 42 years of working and writing with students from all over the world. Her attitude is ever curious. When a student from Afghanistan asked her why she choses to spend time with kids, she answered, “Because I want to remember what you know.”

It was a luminous presentation, full of stories from her 42 years of working and writing with students from all over the world. Her attitude is ever curious. When a student from Afghanistan asked her why she choses to spend time with kids, she answered, “Because I want to remember what you know.”

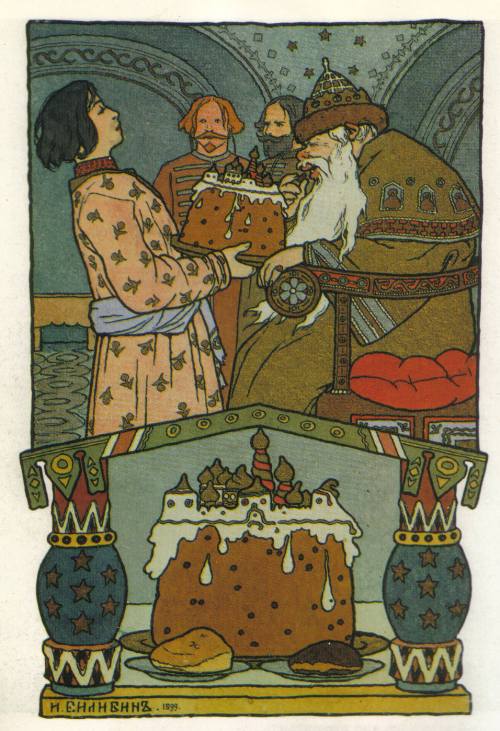

Ivan Bilibin, 1895

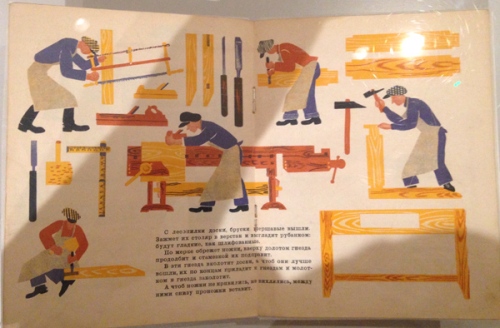

Ivan Bilibin, 1895 Galina and Olga Chichagova, poster design with text by A. Galena, 1925.

Galina and Olga Chichagova, poster design with text by A. Galena, 1925. Eduard Krimmer, How the Whale Got His Throat (Rudyard Kipling) 1926.

Eduard Krimmer, How the Whale Got His Throat (Rudyard Kipling) 1926. Issachar Ber Ryback for In The Forest (Leib Kvitko) 1922.

Issachar Ber Ryback for In The Forest (Leib Kvitko) 1922. Eduard Krimmer, Numbers, 1925

Eduard Krimmer, Numbers, 1925 Vera Ermolaeva, Top-Top-Top (Nikolai Aseev), 1925

Vera Ermolaeva, Top-Top-Top (Nikolai Aseev), 1925 Illustrations for The Flea (Natan Vengrov) by Iurii Annenkov, c. 1918

Illustrations for The Flea (Natan Vengrov) by Iurii Annenkov, c. 1918 Konstantin Rudakov, Telephone, 1926

Konstantin Rudakov, Telephone, 1926 Evgenia Evenbakh, The Table, 1926

Evgenia Evenbakh, The Table, 1926 Aleksandr Deineka, Electrician (B. Uralski), 1930

Aleksandr Deineka, Electrician (B. Uralski), 1930 Tevel Pevezner, The Cow Shed (Evgeny Shvartz), 1931

Tevel Pevezner, The Cow Shed (Evgeny Shvartz), 1931 Tevel Pevezner, The Poultry Yard (Evgeny Shvartz), 1931

Tevel Pevezner, The Poultry Yard (Evgeny Shvartz), 1931

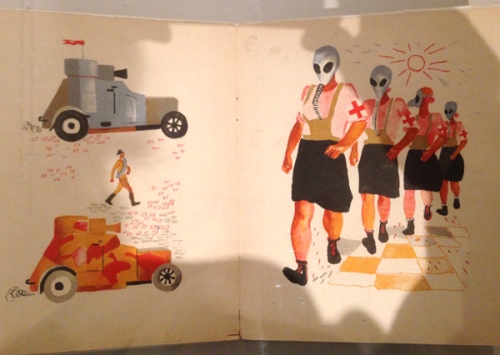

Georgii Echeistov, What It Carries Where It Travels, 1930

Georgii Echeistov, What It Carries Where It Travels, 1930 Unknown illustrator, First Counting Book (F. N. Blekher), 1934

Unknown illustrator, First Counting Book (F. N. Blekher), 1934 Maria Siniakova, Circus (Nikolai Aseev), 1929

Maria Siniakova, Circus (Nikolai Aseev), 1929 Vladimir Lebedev, Circus (Samuil Marshak) 1925

Vladimir Lebedev, Circus (Samuil Marshak) 1925

Vladamir Konashevitz, unpublished illustration for Pictures For Little Ones, 1925

Vladamir Konashevitz, unpublished illustration for Pictures For Little Ones, 1925 Vladamir Konashevitz, Mugs, 1925.

Vladamir Konashevitz, Mugs, 1925. Aleksandr Deineka, The Red Army Parade, 1930

Aleksandr Deineka, The Red Army Parade, 1930