Picture books writers, generally, aren’t doing elaborate character sketches and questionnaires about what secret object their character keeps in the sock drawer, his favorite breakfast food or what her grandfather did for a living. There isn’t going to be time to develop or to even hint at much nuance.

But like most characters, your main character needs to start in one place and end in a different place emotionally. And that not only comes from a change in situation but a change in their character.

So how do you set up a character quickly? I tell my students to think in terms of a core trait. One clear thing you can say about this character after just a few lines.

How would you describe these picture book characters?

“No one ever came to Bear’s house. It had always been that way, and Bear was quite sure he didn’t like visitors. He even had a sign: No Visitors Allowed” (A Visitor for Bear, Bonny Becker)

“No one ever came to Bear’s house. It had always been that way, and Bear was quite sure he didn’t like visitors. He even had a sign: No Visitors Allowed” (A Visitor for Bear, Bonny Becker)

Even if I didn’t know this character (but of course I do since I wrote it!) I’d say grouchy and reclusive. There’s a lot I didn’t know about Bear until Kady MacDonald Denton did her illustrations. For example, I didn’t know that Bear was such a fastidious homebody with his ever-present apron, big fat bottom and delicate paws. Although a lot of character is suggested in the text–Bear is very deliberate about fixing his breakfast, he’s the sort to make tea and he has cozy fires- think the reader has a strong sense of his most important trait from the first few lines.

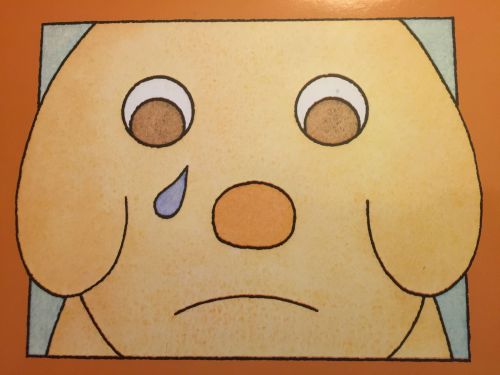

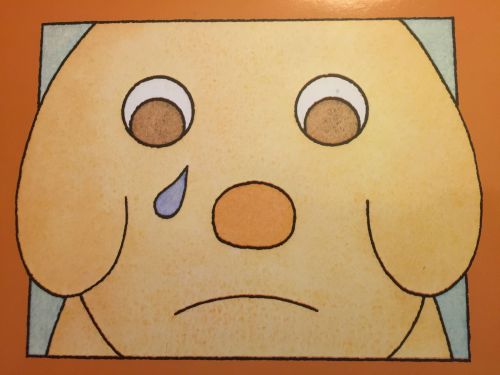

What about this puppy? What’s his core trait.

“I was the last of Momma’s nine puppies.

“I was the last of Momma’s nine puppies.

The last to eat from Momma, the last to open my eyes.

The last to learn to drink milk from a saucer,

The last one into the dog house at night.” (The Last Puppy, Frank Asch)

Well, Asch makes it clear across 8 story pages that if this puppy is anything—it’s last! And he has good reason for beating that point home. I won’t give it away, but it sets up one of the best final twists ever in a picture book.

What can you say about Corduroy from the opening lines?

“Corduroy is a bear who once lived in the toy department of a big store. Day after day he waited with all the other animals and dolls for somebody to come along and take him home.

“Corduroy is a bear who once lived in the toy department of a big store. Day after day he waited with all the other animals and dolls for somebody to come along and take him home.

The store was always filled with shoppers buying all sorts of things but no one ever seemed to want a small bear in green overalls.” (Corduroy, Don Freeman)

Easily overlooked, like so many children? I know that we quickly care for this little bear and want him to get picked. Later in the story, Corduroy is made even more pitiful because his overall strap has broken making him even less desirable and neglected, but that’s just icing on the cake. Right from the start Freeman has tapped into a universal quality. Who hasn’t felt left on the shelf at one time or another.

The thing about a truly outstanding trait is that it carries the story direction and resolution within it. You just know that the last puppy isn’t always going to be last and Corduroy isn’t always going to be overlooked.

What do you know about Lilly from these opening lines?

“Lilly loved school! She loved the pointy pencils. She loved the squeaky chalk. And she loved the way her boots went clickety-clickety-click down the long, shiny hallways.” (Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse, Kevin Henkes)

“Lilly loved school! She loved the pointy pencils. She loved the squeaky chalk. And she loved the way her boots went clickety-clickety-click down the long, shiny hallways.” (Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse, Kevin Henkes)

One word fits Lilly perfectly: exuberant. And, as with all good stories, it’s this very trait that causes her problems. She gets over-exuberant about her purple plastic purse and this causes problems with her teacher. Henke’s book has the longest set-up I’ve ever seen in a picture book. A whopping 500 or so words of what looks to be about a 1,300 to 1,400 word book. It really heightens the emotional trauma of her turning on her beloved teacher. But, really, we get Lilly after just a few words, especially the “clickety-clickety-click” of her boots.

And then there’s Daisy.

“You must stay close, Daisy,” said Mama Duck.

“You must stay close, Daisy,” said Mama Duck.

“I’ll try,” said Daisy.

But Daisy didn’t. “Come along Daisy!” called Mama Duck.

But Daisy was watching the fish.” (Come Along Daisy, Jane Simmons)

Everyone knows a Daisy. She’s an easily distracted child. But notice how much those few words “I’ll try” do for this story. It makes Daisy a likable character. She’s not willfully disobedient, but she’s not able to promise for sure, either. And she won’t lie about it. Take out the “I’ll try.” And you have a different Daisy.

How about this classic opening? In some ways it doesn’t look like much:

“In the great forest a little elephant is born. His name is Babar. His mother loves him very much. She rocks him to sleep with her trunk while singing softly to him.

“In the great forest a little elephant is born. His name is Babar. His mother loves him very much. She rocks him to sleep with her trunk while singing softly to him.

Babar has grown bigger. He now plays with the other little elephants. He is a very good little elephant. See him digging in the sand with his shell.” (The Story of Babar, Jean de Brunhoff)

Well, here’s an opening that would probably land this book in the editor’s trash today. Look at that clumsy jump in time. “Babar has grown bigger.” Boom! That’s it? And where the heck is this story going anyway. But it doesn’t matter because in the next two lines Babar’s mother is shot dead and he’s launched into a completely different story. De Brunhoff spends little time getting Babar on his way, but even so we learn several critical things about Babar. He’s happy and he’s good but the key trait is that he is loved. This is why the reader feels for him as he goes away from his home and then comes back.

So, do your characters have a key trait? It’s not that you can’t get some nuance and depth in, but what can be said about your character after the first two paragraphs?

Just for fun, to see the power of a core trait, you might try an exercise. Take a few rather bland lines. For example:

Cat went to the forest. It was dark. Cat walked into the forest.

Now add a trait:

Scaredy Cat went to the forest. It was dark. Scaredy Cat walked into the forest.

Brave Cat went to the forest. It was dark. Brave Cat walked into the forest.

Hungry Cat went to the forest. It was dark. Hungry Cat walked into the forest.

Just one word suggests a different character and a different story line. And, if I’m really doing my job, that trait starts to drive all my word choices.

Scaredy Cat went to the forest. It was so dark. Scaredy Cat shivered and slunk into the forest.

Brave Cat went to the forest. It was dark. So what? Brave Cat sauntered into the forest.

Hungry Cat went to the forest. It was dark. Just right. Hungry Cat crept into the forest.

And the story starts to unfold. That’s the power of finding a simple trait for your character.